Unjust ideological fantasies from Putin

The Bretton Woods Conference of 1948 established three key organisations tasked with leading global economic sustainability and preventing the recurrence of global wars. These institutions, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the United Nations, were central to implementing international relations ideologies, fostering unity, and encouraging economic integration through the Marshall Plan, which sought to rebuild Europe and exploit Africa’s natural resources.

Following the formation of these multilateral organisations, European leaders recognised the need for a robust framework to ensure the success of the Marshall Plan and to prevent future destruction from civil, global, or ideological wars.

This gave rise to a pro-European, pan-European approach, strengthening integration through initiatives like the twinning of towns across different European countries. The foundational principles of what would become the European Union were rooted in the ambition to eradicate war on the continent. In parallel, the formation of NATO aimed to prevent any future militarisation on European soil.

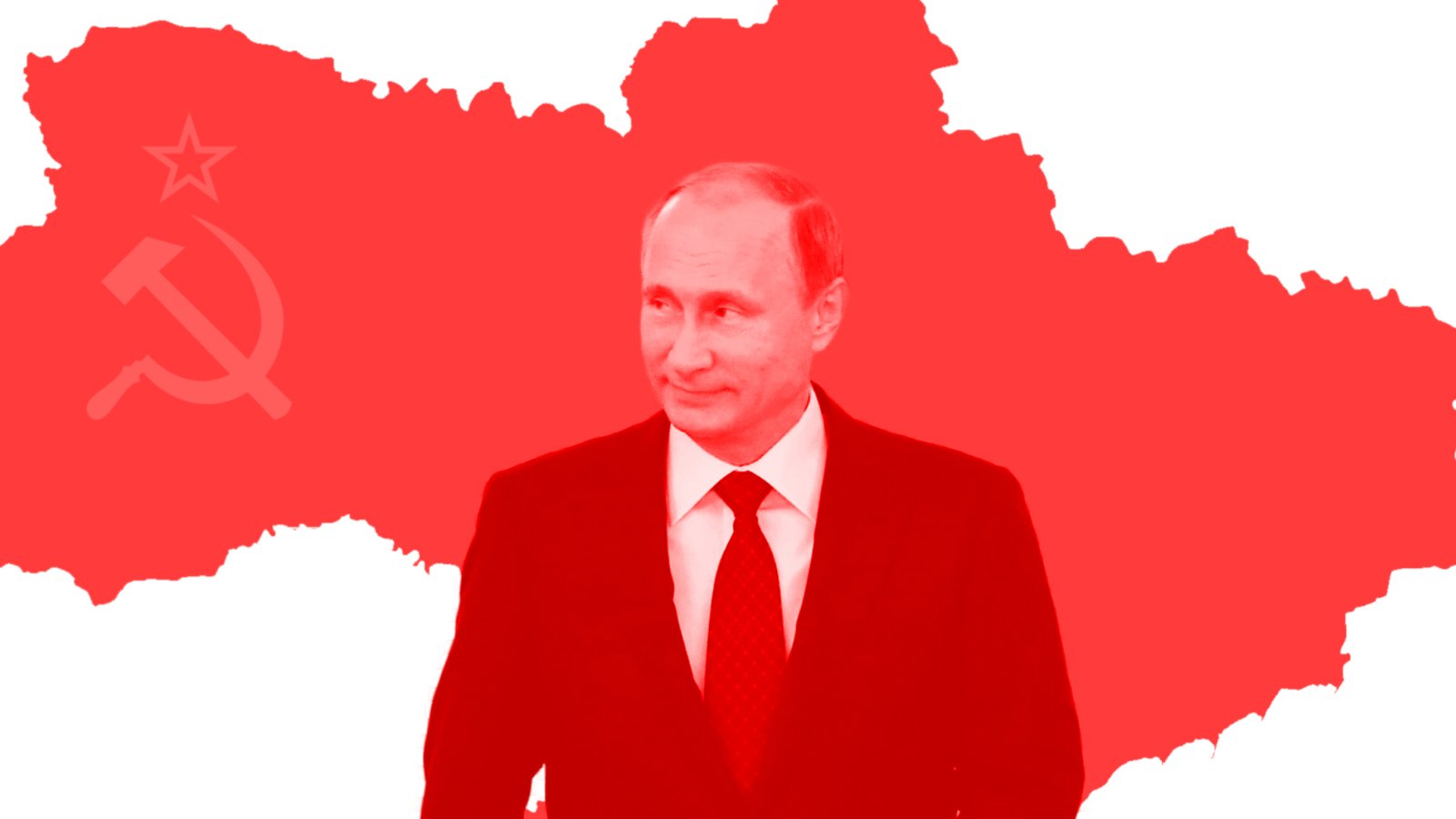

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of Soviet occupation in East Germany marked the decline of one of modern history’s most formidable regimes. The dissolution of the USSR signalled the demise of large-scale communism and ushered in a shift that Russia had not sought. The collapse of the Soviet Union marked the beginning of a new era dominated by capitalism and an increasingly one-sided political and economic rivalry between the US and Russia. This imbalance has long irked President Putin and shaped his increasingly antagonistic worldview.

Putin’s policies and ideological stances are often viewed as extreme, and his authoritarian governance raises deep concerns. Yet, some argue that Western hostility towards him may colour the commentary around his leadership. His admiration for Stalin-era policies is evident, with a leadership style marked by simplification and control. While the reformation of the Soviet Union is unlikely, the idea lingers in political discourse within his regime.

The USSR did not collapse solely because of external pressure; it fell due to internal failings, including weak leadership and the absence of sustainable policies capable of maintaining parity with the US during the Cold War.

The relationship between communism and socialism is not merely ideological; both aim to create systems where cooperation supersedes greed. Yet socialism cannot thrive without cohesion and integration. The dissolution of the USSR stemmed from a belief that capitalism offered a better model, an idea pushed strongly by the United States.

The pain of that separation still resonates in Russia. While Putin may attempt to mirror Stalin’s Soviet Union, his ideology is fundamentally incompatible with global democratic principles. The dream of a reconstituted Soviet bloc is unrealistic, former member states now hold vastly different values and priorities.

The spectre of war is not exclusive to communism; capitalism, too, has its entanglements with military conflict. But the romanticisation of war often stems from authoritarian leaders who believe they can dominate both people and geopolitics. Putin has been portrayed as a destructive strategist, capable of large-scale militarisation. However, in reality, he is constrained. He knows the European Union is bound by treaties and agreements that prevent unauthorised conflict, and that multilateral frameworks exist to deter illegal wars.

For a war to be legitimate, it must be sanctioned; there must be legal justification. United Nations resolutions remain among the strongest tools to authorise the use of force in humanitarian or peacekeeping interventions.

The invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine are examples of unsanctioned military aggression. While force is being used, these wars lack international approval. Crucially, they are unlikely to escalate beyond regional borders, largely due to the threat of global sanctions.

Waging war today is complex; it invites backlash from domestic populations and the international community alike. The idea of a Third World War, once revived by commentators following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, should be discarded. Such a conflict is highly improbable in today’s interconnected and regulated world. We live in an age defined by globalisation, and with it comes a system of checks and balances that renders full-scale global war a relic of the past.