Maybe we should blame the parent.

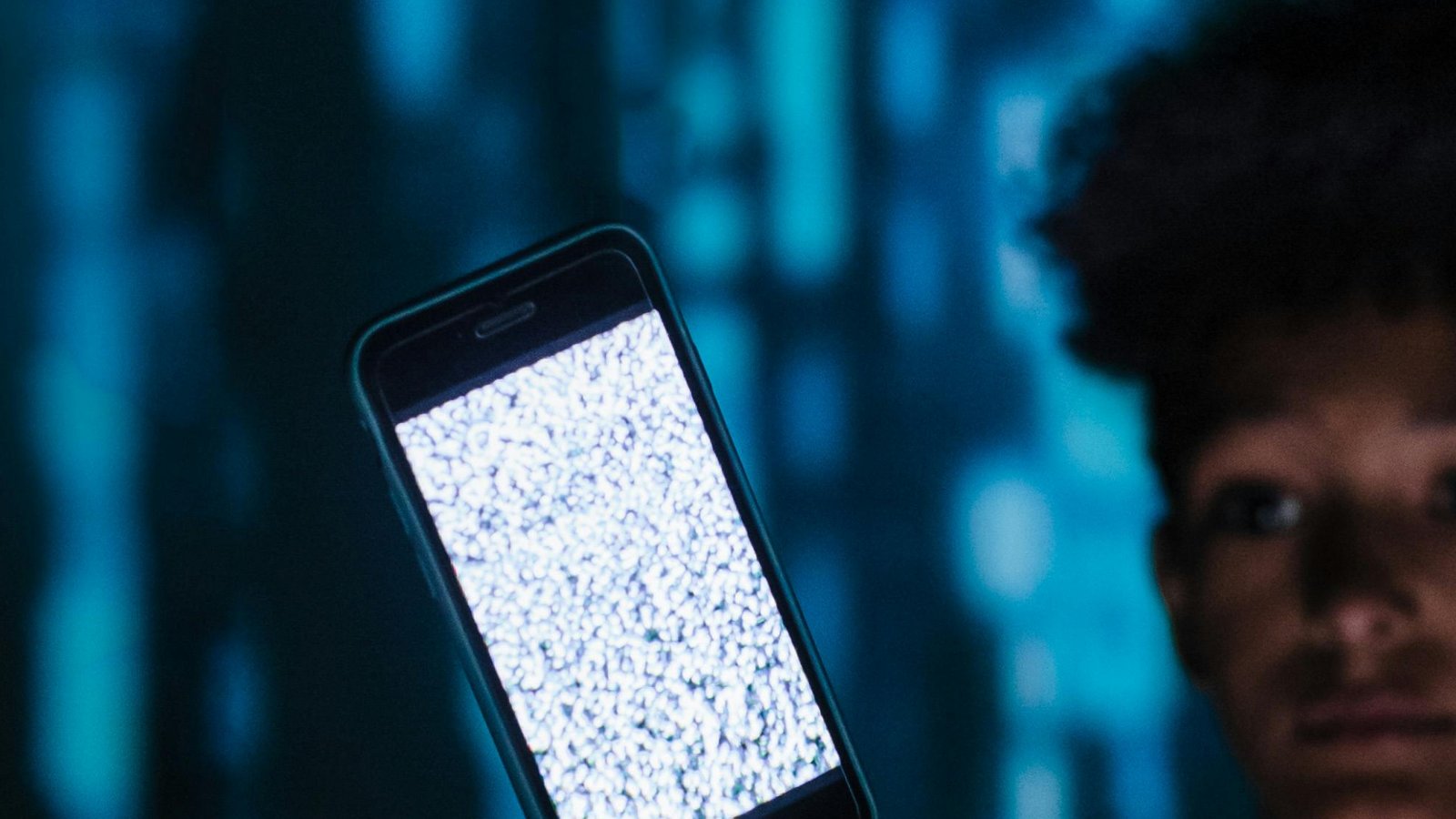

The Economist published an article which reiterates the influence of kids on social media with the rise of kid influencers in America. This epidemic is going to spread across the globe, and it is obvious that it is going to transpire in the English-speaking nations first before it gets to the non-English-speaking nations. Most kids have smartphones nowadays, and smartphones and tablets have become the first things on their birthday and Christmas wishlists. YouTube Shorts and TikTok provide short-attention-span videos that do not explore their cognitive load, and they allow children to scroll through content without looking at the creativity of that content.

Kid influencers are influencing other kids to be like them, and this has made kids entitled to materialistic things. Maybe we need to reconsider how we teach our children and promote a culture which enables children to become altruistic in their approach to worldly things that their parents cannot afford.

This growing trend highlights a concerning shift in childhood values. Social media platforms, especially those dominated by short-form video like TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts, have redefined what children aspire to be. Where once role models might have been athletes, scientists, or community leaders, today many children idolise peers their age who showcase extravagant lifestyles, branded clothing, and constant product hauls. These images, often curated and staged, present a false reality that fuels envy, unrealistic expectations, and dissatisfaction with one’s own life.

The danger lies not only in what these children see, but in how frequently they consume it. Social media is designed to be addictive. Algorithms serve up endless streams of dopamine-triggering content, training young minds to crave constant stimulation. The more they watch, the more they compare themselves to these online personalities, and the more they develop a sense of entitlement, believing they, too, should have the same luxuries without understanding the work, luck, or sometimes manipulation behind those lifestyles.

Smartphones have become the new currency of childhood status. A decade ago, a bike or a dollhouse might have been the highlight of a child’s wish list. Now, the latest iPhone or a high-end tablet is considered a “necessity” for social belonging. Parents often find themselves pressured to keep up, not because their children need these devices for genuine educational purposes, but because they fear their child will be excluded from the digital playground where friendships and reputations are now built.

The concept of “kid influencers” intensifies this cycle. A child who gains followers for showing off expensive toys, designer outfits, or exotic vacations sends a powerful yet damaging message: self-worth comes from possessions and popularity metrics, not from kindness, creativity, or personal achievements. This breeds a generation that values likes over learning, and consumerism over character.

To address this, society needs a cultural reset. Parents, educators, and community leaders must unite to teach children the difference between real life and online performance. We need to promote digital literacy from an early age, not just teaching kids how to use devices, but how to critically evaluate what they see, understand the motives behind influencer marketing, and resist the pull of algorithmic addiction.

Most importantly, we need to instil altruism as a counterweight to materialism. Encouraging children to volunteer, engage in creative projects, and appreciate what they already have can shift their focus from “What can I get?” to “What can I give?” This is not just a parental responsibility but a societal one, requiring media campaigns, school programs, and perhaps even tighter regulations on marketing aimed at minors.

If left unchecked, social media addiction will continue to mould children into consumers first and humans second. The spoiled behaviour we see today is not just an accident; it is the predictable outcome of an attention economy that profits from their desires. We must decide, collectively, whether we want the next generation defined by generosity and resilience or by greed and entitlement.